Unmasking the Hidden Truths of Human Trafficking in South Africa

Trafficking isn’t always about dark alleys and kidnappings. Sometimes, it looks like a promise of work, love, or education. Sometimes, it’s the neighbour you trust. Sometimes, it looks like a promise of work, love, or education. Sometimes, it’s the neighbour you trust. Always, it’s the horror of being treated as nothing more than a body to exploit.

To shed light on one of the fastest-growing crimes in South Africa, we sat down with Celeste from TEARS Foundation to separate myth from reality, explore the lived experiences of survivors, and highlight what every South African can do to fight trafficking.

When people hear “human trafficking,” many imagine kidnappings. Why is that perception misleading?

People want to believe things that make them feel safe, but actually that is one of the most dangerous myths. People think of dramatic abductions in films, when in reality most victims are lured in through trust. It could be someone you know, a boyfriend, a neighbour, or someone offering you a job or scholarship. Trafficking generally hides in plain sight, because it doesn’t always look like crime at first. Survivors often disclose that they only realised they were being trafficked when they were already trapped.

If it’s not just kidnappings, what does trafficking look like on the ground in South Africa?

In South Africa, trafficking has many faces. Women and children forced into sexual exploitation, men locked in factories or farms working long hours for no pay, domestic workers held in houses where they’re never allowed to leave. There are also horrific cases of trafficking for body parts, where vulnerable people are targeted for ritual killings or organ trade.

In just the past year, South Africa has seen a string of shocking trafficking cases that reveal how close to home the crisis really is. Seven Chinese nationals were sentenced to 20 years each for forcing 91 Malawians into slave-like factory labour in Johannesburg; in the Western Cape, the heartbreaking Joshlin Smith case saw her mother and others jailed for life for trafficking the six-year-old child, allegedly sold for body parts; in Sandringham, Johannesburg, police uncovered 60 Ethiopians held in a bungalow under brutal conditions; and earlier in Durban, more than 200 Myanmar nationals were rescued from a ship in one of the largest trafficking busts on South African soil.

What tactics are traffickers using today, particularly around grooming and false promises?

Traffickers are skilled manipulators. They dangle hope, and that is the scary part of the process; promises of love, jobs, education, or a way out of poverty. Once someone is hooked, traffickers tighten control: taking away ID documents, isolating them from family, loading them with fake “debts,” threatening violence against loved ones. Survivors often describe it as wearing “invisible chains.” They may not be tied up, but their freedom is completely stolen. It is sometimes hard to recognise because it is not always a case of people clearly being held against their will.

Who is most vulnerable, and why? Are there patterns in who traffickers target?

Vulnerability is the trafficker’s playground. Poverty, unemployment, being far from home as a migrant, or living with the scars of gender-based violence, these are all the open doors traffickers exploit. In South Africa, women and girls are often forced into sexual exploitation, while men and boys are pushed into hard, unpaid labour. In extreme cases, even the most vulnerable; street children, people living with disabilities, or the very poor, are targeted for body part trafficking. Traffickers exploit those who already feel invisible.

What are some myths you wish we could dispel once and for all about trafficking?

- That trafficking is only about sex. It’s not. Labour trafficking, domestic servitude, and body part trafficking are also major problems, though they’re often invisible.

- That victims could “just walk away.” In truth, they’re controlled by fear, threats, or debts. Leaving can feel more dangerous than staying.

- That it happens somewhere else. South Africa is a source, transit, and destination country. It’s here, whether we see it or not.

Once survivors escape, what systemic challenges stop them from getting justice or protection?

Leaving is only the first step, and it’s often terrifying. Survivors usually have no ID, no money, nowhere to go. They might be addicted, co-dependent, and have lost trust in anyone trying to help them. They fear retaliation from traffickers, who may threaten their families. And even when they reach out, the system doesn’t always work as it should.

We do have a national referral pathway that’s meant to connect survivors to health, justice, and social services. But in reality, it’s not consistently used, and too many survivors fall through the cracks.

What changes do you believe would make the biggest difference in fighting trafficking?

First, we need frontline responders to work together, police, healthcare workers, labour inspectors need to be able to recognise trafficking quickly and know how to act. Every hour counts. Survivors need trauma-informed care, understanding, and long-term rehabilitation. Too often, systems retraumatise instead of helping. We need communities to believe survivors, not blame or shame them. If we close the gap between the law on paper and the response on the ground, we can save lives.

For people reading this article: what signs should we watch for, and what is the safest way to respond if we suspect trafficking?

There are always red flags if you look closely:

- Someone who is never allowed to be alone, always monitored.

- People who don’t control their ID, passport, or phone.

- Someone giving rehearsed or “scripted” answers about why they’re here.

- Living and working in the same place, often under watch.

- Talking about paying off endless “debts” to recruiters.

If you notice these, don’t confront the trafficker. It can endanger both you and the victim. Instead, write down details (place, time, names) and report the incident.

What misconceptions around trafficking do you think actually put survivors at greater risk?

Two big ones:

- Believing victims can just leave, which ignores the threats, debts, and fear holding them captive.

- Thinking trafficking only happens in brothels. That makes us blind to the factories, farms, hotels, private homes, and even ritual crimes where body parts are taken. Those blind spots allow traffickers to keep operating.

And finally, how can everyday South Africans stand with survivors and support TEARS in this fight?

Save the numbers: 0800 222 777 for the national trafficking hotline, and 08000 83277 / *134* 7355# for TEARS’ GBV support. Share real, credible information. Bust myths in your circles. Talk to your children. Bring the conversation into workplaces, churches, and community meetings.

Lastly, support survivor services. TEARS Foundation is on the ground every day offering a lifeline, trauma counselling, referral pathways, and case management services. Every donation, every partnership, every voice raised helps us protect more people.

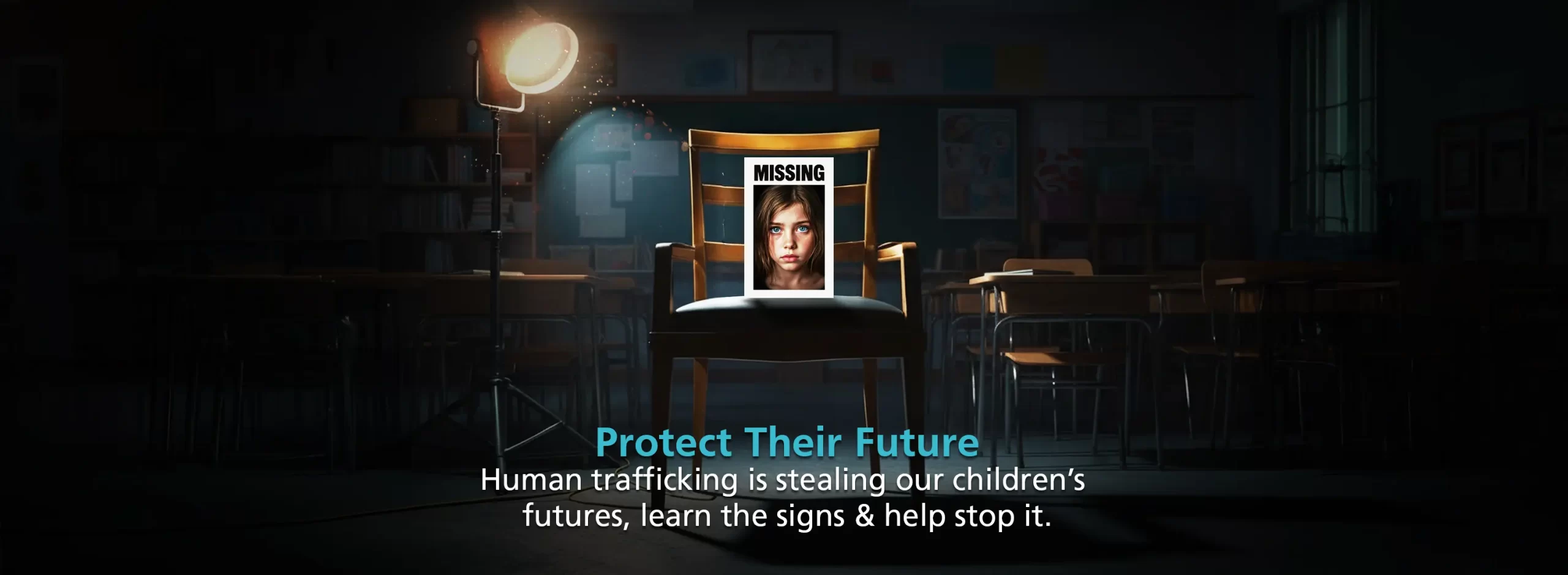

Human trafficking thrives in silence, myths, and blind spots. The more we speak, share, and act, the less space traffickers have to operate. When we acknowledge trafficking in all its forms, from sexual and labour exploitation to body part trafficking, we strip away the shadows that allow it to survive.

Every South African has a role to play. Educate. Report. Support. Fund. And most importantly, believe survivors. Together, we can unmask trafficking and protect those who need it most.